After a long crawl, through a narrow cave, in the hills of Jammu, you finally arrive at Vaishnodevi, embodied as three outcroppings of rock, draped with red cloth with gold tassels, flowers, with umbrellas hanging from above. These three rocks represent Mahalakshmi, Mahasaraswati, and Mahakali, the three forms of the Goddess. The air is rent with the jubilant cries of devotees, ‘Jai Mata Di,’ which is Punjabi for ‘Jai Mata Ki’, or ‘Victory to the Mother Goddess’. It is important to clarify this, as many erroneously assume that ‘di’ is a proper noun, a local name of the Goddess, rather than a preposition.

Vaishnodevi is now a very popular place of pilgrimage. She is one of the many mountain goddesses found in the Punjab and Jammu regions. Some identify her as part of the seven sisters, or seven maidens, who are part of Indian folklore; mysterious women who run in the forest, unattached to any man, and who can be dangerous, if threatened, and benevolent, if appeased. The image of the seven maidens has been traced to the Indus Valley cities that thrived over 3,000 years ago.

Who are these seven sisters? Are they the matrikas, the female forms of male gods: Shivani from Shiva, Vaishnavi from Vishnu, Vinayaki from Vinayaka, Kumari from Kumara, Indrani from Indra, Varahi from Varaha, Narasimhi from Narasimha? Are they the Pleiades constellation, the Krittikas, who are collectively known as the mother of Shiva’s warlord son, Kartikeya? Were they once the wives of the Sapta Rishis? Were they the ancient goddesses of the forest and rivers?

In Maharashtra, they are known as ‘sati asara’, seven stones, worshipped by women who have trouble conceiving, and pregnant women who fear miscarriage, and women whose children have viral fever with skin rashes. We cannot be sure. Textual references give us tantalizing glimpses of a long oral tradition that glides along the rivers and plains of India, whispered for millennia by common folk, who have either chosen to stay away from, or have been kept out of, orthodox Sanskrit Brahminical traditions.

What is most peculiar about the Vaishnodevi Temple is that, like many goddesses of the Punjab and Jammu regions, she is worshipped as a vegetarian goddess. Typically, in Puranic and tantric traditions, the Goddess is worshipped with blood sacrifice. During Navaratri, the festival of the nine nights celebrated in spring (vasant) and autumn (sharad), when she battles the asuras, the Goddess is offered the blood of buffaloes, goats, and roosters. But not at Vaishnodevi, where the Goddess is strictly vegetarian, an idea that may disconcert a Shakta from Bengal, Assam or Odisha.

When the old Vedic ritual ways gave way to the Puranic traditions, two gods emerged who competed for supremacy: Shiva and Vishnu. Shiva embodied the monastic side of Hinduism, while Vishnu embodied the householder side. Shiva overtly challenges Vedic orthodoxy. In his tales, he beheads Brahma and Daksha. Vishnu also challenges Vedic orthodoxy, but covertly, as the royal Ram and the pastoral Krishna. Tensions remain between the two schools of thought. Shiva is increasingly associated with tantric practices, especially the ritual use of alcohol, meat, and sex, and Vishnu with milk, cows, vegetarianism, and continence. Shiva’s followers speak of siddha, or magical powers obtained through yogic practices. Vishnu’s followers speak of dharma, or governance of society. Shiva withdraws from the world. Vishnu engages with the world.

It is the Goddess who reconciles the two deities. As Shakti, she becomes Shiva’s wife, turns the fierce hermit into the docile householder. As Lakshmi, she becomes Vishnu’s responsibility, forcing him to descend from his high heaven of Vaikuntha, and participate in human affairs through the avatars Ram and Krishna. These tales emerged about a thousand years ago and it is these cultural shifts that help us understand the shrine of Vaishnodevi.

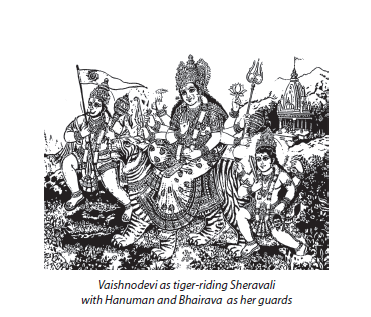

Vaishnodevi is also identified as a princess from the south of India, who encounters Ram and wishes to marry him, but Ram is ekam-patnivrata, faithful to a single wife, Sita. He tells her that he cannot marry her as Ram, but in a future life will surely be her husband. So the princess moves to the mountain and becomes a hermit. She is sometimes identified as Trikuta, and sometimes as Vedavati. Ravana, a worshipper of Shiva, tries to make her his wife, but she enters the holy fire, and is reborn as Vaishnodevi, meditating and waiting for Ram to return as a future avatar of Vishnu. While meditating, she draws the attention of Bhairava, who follows tantric rituals, and asks the Goddess for food. She feeds him. But for him ‘food’ includes sex (maithuna in tantric rituals). This the Goddess refuses. She informs Bhairava that she is waiting for Ram, and he should respect her wishes. But Bhairava refuses and tries to force his will upon her. The Goddess runs away from him and the path she takes is the path taken by pilgrims today. Bhairava pursues her, fighting Langur-vira, the monkeyhero, who tries to stop him. Some people identify Langur-vira as Hanuman. Finally, exasperated by his pursuit, the Goddess turns around and takes the form of Chandi, the fierce one, and beheads Bhairava. His body remains on the mountain and turns into a boulder, which can still be seen today. His head falls in the valley below. Bhairava repents and apologizes for his transgression. ‘A son can be a bad son, but a mother cannot be a bad mother,’ he says. Vaishnodevi calms down and forgives him and declares that her worshippers will visit his shrine too, where his head will be worshipped, as it is even today.

Thus, we see a story that involves the three streams of Puranic thought: Shakta, Shaiva, and Vaishnava. Here the Shakta tradition aligns with the Vaishnava tradition of Ram, and shuns the Shaiva tradition of Bhairava. But eventually, all is reconciled. Bhairava is punished but also forgiven and finally venerated. This transformation of Bhairava is something that is unique to Hindu culture, where no one is a ‘villain’ in the eyes of God. Everything changes—even those who ignore the consent of the Goddess are forgiven, and given respect, after due repentance and admonishment.

Learn more here