It’s been many years since Sher Singh, of village Solti, came to my rescue.

At the time I was living right at the top of the Landour hill, in a rented cottage that leaked badly. It was cold that winter and I was short of funds and in need of sustenance. And to make matters worse, our new Prime Minister, a strict moralist who knew what was good for everyone, had imposed prohibition on the country, and I was suffering from the non-availability of Solan No1 (a cheap but good whisky) and a certain XXX Rum that had been distilled at Rosa in UP since before the 1857 revolt. The distillery had changed hands more than once during the fighting, and both oppressors and oppressed had raided it until it was emptied of its energizing grog. It had recovered from those traumatic events; but now, in more peaceful times, it was to suffer again, along with those, such as this writer, who thirsted after the mellowed and matured juices of our all-purpose sugarcane.

Sher Singh was my milkman. Early every morning he trudged up the hill from his village, three miles distant, to deliver his milk to two or three homes on the hillside. On the way he watered it a little at a roadside hydrant; but it was good milk, once you had removed some of the grass that floated around in the can.

One morning, when Sher Singh found me sitting in the sun looking rather depressed, he offered condolences, well knowing the reason for my dejection.

‘Not to worry, sir,’ he said, ‘When one door closes, another door opens. Every problem has its solution. In three days’ time I will have solved your problem.’

Three dry and thirsty days passed. Sher Singh came and went. On the fourth morning he asked me for my hot-water bottle — one of those rubber bags which keep you warm for half the night, allowing you to freeze during the second half.

Anyway, I gave him my hot-water bottle. His need, I felt sure, was greater than mine.

‘Do you have another?’ he asked.

This was testing my generosity, but I was in a don’t-care-mood, and I said, ‘To hell with it,’ and gave him the second bottle.

Next morning he turned up with both bottles. They were full of something; certainly not milk.

‘Don’t you want them?’ I asked.

‘See if you like my home-made brandy,’ he said, and unscrewing one of the bottles, he poured a vile-looking liquid into an empty jug.

‘Go on, taste it,’ he said.

I did as I was told. It tasted awful — a combination of turnips and castor oil—but it lit a small fire in my stomach, and I came to life immediately.

Sher Singh had created his own still and was busy producing a potent and heady liquor for all his friends — and customers.

The hillside came to life. A somnolent Landour became a merry mountain. Strengthened and uplifted, the more adventurous residents of Landour—missionaries, retired colonels and brigadiers, schoolteachers, shopkeepers and the odd hippie (left over from the sixties) — found themselves immune to the mists of February and sharp winds of March.

We flung aside restraint. Mischief abounded. A respectable headmistress fell in love with a muleteer, and rode off with him to his village near Harsil. A retired vice-admiral drank too much one evening and performed a sailor’s jig in the middle of the Upper Mall. A judge had an affair with the dhobi’s sister, and the local padre developed acute peritonitis and perished from a burst appendix. Not all was merriment in the spring of 1980.

A posse of policemen was sent down to Solti village to find out what was going on down there. They were not seen for several days. After being entertained by Sher Singh and his friends, they had lost their way coming back, and had emerged near the Yamuna bridge, happy to be alive in spite of severe hangovers.

I spent most of my evening in the company of a famous shikari, who was paying me to write his memoirs. He made up most of his exploits, but it was fun anyway, and after consuming a hot-water bottle of firewater, we saw pink elephants and purple tigers.

Then suddenly this orgy of wine, women and song came to an end. Sher Singh’s supply system had broken down. Our hot-water bottles were dry and empty.

There was no sign of Sher Singh, either.

I decided to go down to his village. Landour was in suspense.

I was in my forties then, still quite agile on a mountain slope, and it took me a little over an hour to scramble down the steep footpath to Solti village.

I found Sher Singh on his cot, his arm in a sling, his head bandaged, strips of plaster on his hands and feet. He had just been carried home, piggyback on a neighbour’s shoulder, from the mission hospital.

‘The bear attacked me,’ he explained. ‘It had been raiding my still every evening, and it was becoming a nuisance—getting drunk and chasing the women as they returned from the fields.’

Armed with a lathi, Sher Singh had attempted to chase away the bear, but it had turned on him, using its claws to good effect before taking off into the forest. Lucky to be alive, Sher Singh would carry the scars for the rest of his life.

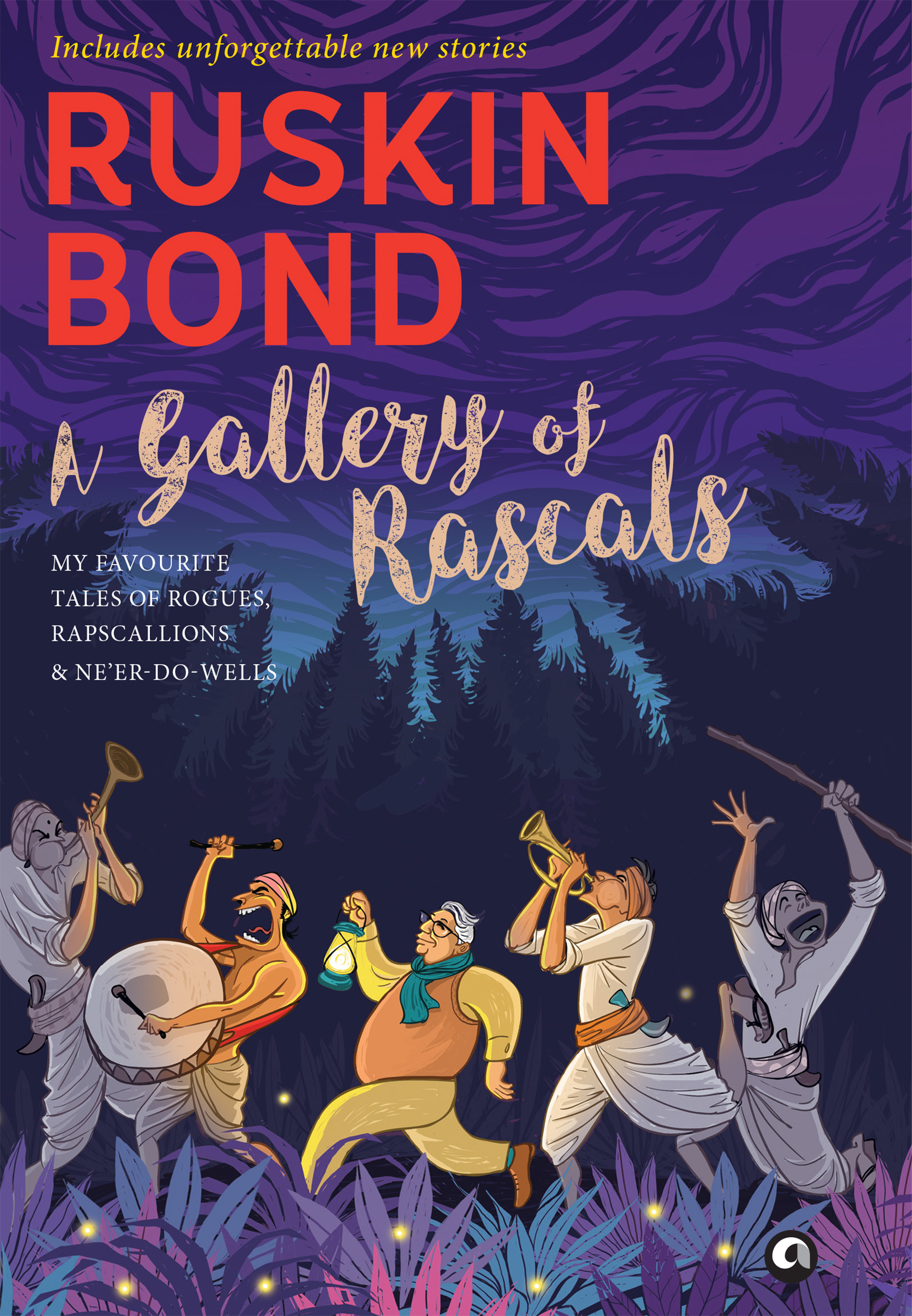

I was reluctant to trudge back to Landour on my own. I had no desire to encounter an alcoholic bear on the way. Deprived of Sher Singh’s magic potion, it would be in a bad mood. Fortunately, several of the young men of the village offered to escort me home, and we went uphill in style, making a lot of noise to keep the bear away. One youth beat a drum, another blew a bugle, and a third shouted imprecations against bears in general.

The flow of high-spirited spirits having come to a halt, Landour returned to its sober and sombre self. The headmistress returned from Harsil as though nothing unusual had happened, the retired judge fell out of love with the dhobi’s sister, and a new padre moved into the parson’s house.

Fortunately for some of us, the government in Delhi changed around that time, and the prohibition law was repealed. ‘Foreign liquor’ (as made in India) appeared again in the stores, and the vendors of home-made spirits went out of business. My hot-water bottles were put to their legitimate use.

When Sher Singh recovered from his wounds he continued to deliver my milk, and did so for many years, always watering it down a little at the tap near Sisters’ Bazaar. Then he grew too old to climb up to Landour, and I grew too old to scramble down to his village. But his grandson now delivers the milk on his way to school, and being a good boy, he doesn’t water it down.

The other day he told me that his grandfather was feeling the cold. It has been a harsh winter. So I sent the old man one of my hot-water bottles. And for old times’ sake, I filled it with the better part of a bottle of rum.

Get your copy of A Gallery of Rascals here