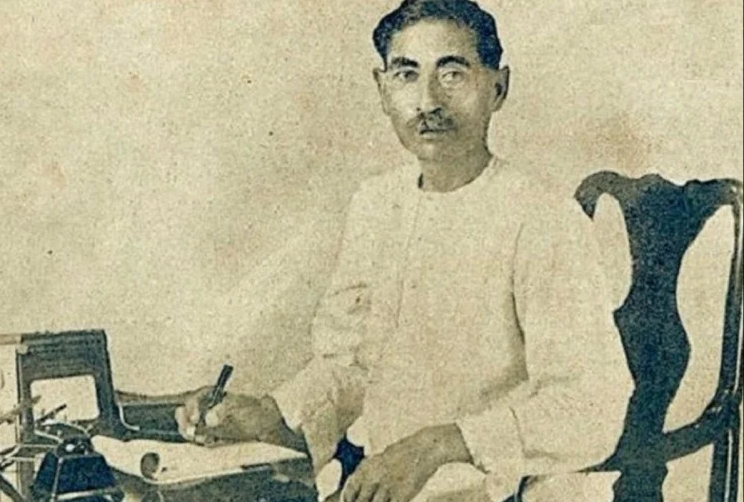

On the occasion of Eid al-Adha and Munshi Premchand’s birth anniversary, we bring to you one of Premchand’s most loved stories, ‘Idgah’.

Premchand (Dhanpat Rai Srivastav, 1880-1936) was one of India’s greatest writers. He wrote in Hindi and published over a dozen novels and nearly 300 short stories.

A full thirty days after Ramadan comes Eid. How wonderful and beautiful is the morning of Eid! The trees look greener, the fields more festive, the sky has a lovely pink glow. Look at the sun! It comes up brighter and more dazzling than before to wish the world a very happy Eid. The village is agog with excitement. Everyone is up early to go to the Idgah mosque. One finds a button missing from his shirt and is hurrying to his neighbour’s house for thread and needle. Another finds that the leather of his shoes has become hard and is running to the oil-press for oil to grease it. They are dumping fodder before their oxen because by the time they get back from the Idgah it may be late afternoon. It is a good three miles from the village. There will also be hundreds of people to greet and chat with; they would certainly not be finished before midday.

The boys are more excited than the others. Some of them kept only one fast—and that only till noon. Some didn’t even do that. But no one can deny them the joy of going to the Idgah. Fasting is for the grownups and the aged. For the boys it is only the day of Eid. They have been talking about it all the time. At long last the day has come. And now they are impatient with people for not hurrying up. They have no concern with things that have to be done. They are not bothered whether or not there is enough milk and sugar for the vermicelli pudding. All they want is to eat the pudding. They have no idea why Abbajan is out of breath, running to the house of Chaudhry Karim Ali. They don’t know that if the chaudhry were to change his mind he could turn the festive day of Eid into a day of mourning. Their pockets bulge with coins like the stomach of the pot-bellied Kubera, the Hindu God of Wealth. They are forever taking the treasure out of their pockets, counting and recounting it before putting it back. Mahmood counts ‘One, two, ten, twelve’—he has twelve paise. Mohsin has ‘One, two, three, eight, nine, fifteen’ paise. Out of this countless hoard they will buy countless things: toys, sweets, paper-pipes, rubber balls—and much else.

The happiest of the boys is Hamid. He is only four, poorly dressed, thin and famished-looking. His father died last year of cholera. Then his mother wasted away and, without anyone finding out what had ailed her, she also died. Now Hamid sleeps in Granny Ameena’s lap and is as happy as a lark. She tells him that his father has gone to earn money and will return with sack loads of silver. And that his mother has gone to Allah to get lovely gifts for him. This makes Hamid very happy. It is great to live on hope; for a child there is nothing like hope. A child’s imagination can turn a mustard seed into a mountain. Hamid has no shoes on his feet; the cap on his head is soiled and tattered; its gold thread has turned black. Nevertheless Hamid is happy. He knows that when his father comes back with sacks full of silver and his mother with gifts from Allah he will be able to fulfil all his heart’s desires. Then he will have more than Mahmood, Mohsin, Noorey and Sammi.

In her hovel the unfortunate Ameena sheds bitter tears. It is Eid and she does not have even a handful of grain. If only her Abid were there, it would have been a different kind of Eid!

Hamid goes to his grandmother and says, ‘Granny, don’t you fret over me! I will be the first to get back. Don’t worry!’

Ameena is sad. Other boys are going out with their fathers. She is the only ‘father’ Hamid has. How can she let him go to the fair all by himself? What if he gets lost in the crowd? No, she must not lose her precious little soul! How can he walk three miles? He doesn’t even have a pair of shoes. He will get blisters on his feet. If she went along with him she could pick him up now and then. But then who would be there to cook the vermicelli? If only she had the money she could have bought the ingredients on the way back and quickly made the pudding. In the village it would take her many hours to get everything. The only way out was to ask someone for them.

The villagers leave in one party. With the boys is Hamid. They run on ahead of the elders and wait for them under a tree. Why do the oldies drag their feet? And Hamid is like one with wings on his feet. How could anyone think he would get tired?

They reach the suburbs of the town. On both sides of the road are mansions of the rich, enclosed all around by thick, high walls. In the gardens mango and lichi trees are laden with fruit. A boy hurls a stone at a mango tree. The gardener rushes out screaming abuses at them. By then the boys are a furlong out of his reach and roaring with laughter. What a silly ass they make of the gardener!

Then come big buildings: the law courts, the college and the club. How many boys would there be in this big college? No, sir, they are not all boys! Some are grown-up men. They sport enormous moustaches. What are such grown-up men going on studying for? How long will they go on doing so? What will they do with all their knowledge? There are only two or three grown-up boys in Hamid’s school. Absolute duds they are too! They get a thrashing every day because they do not work at all. These college fellows must be the same type—why else should they be there! And the Masonic Lodge. They perform magic there. It is rumoured that they make human skulls move about and do other kinds of weird things. No wonder they don’t let in outsiders! And the white folk play games in the evenings. Grown-up men, men with moustaches and beards playing games! And not only they, but even their memsahibs! That’s the honest truth! You give my granny that something they call a racket; she wouldn’t know how to hold it. And if she tried to wave it about she would collapse.

Mahmood says, ‘My mother’s hands would shake; I swear by Allah they would!’

Mohsin says, ‘Mine can grind maunds of grain. Her hand would never shake holding a miserable racket. She draws hundreds of pitchers full of water from the well every day. My buffalo drinks up five pitchers. If a memsahib had to draw one pitcher, she would go blue in the face.’

Mahmood interrupts, ‘But your mother couldn’t run and leap about, could she?’

‘That’s right,’ replies Mohsin, ‘she couldn’t leap or jump. But one day our cow got loose and began grazing in the chaudhry’s fields. My mother ran so fast after it that I couldn’t catch up with her. Honest to God, I could not!’

So they proceed to the stores of the sweetmeat vendors. All so gaily decorated! Who can eat all these delicacies? Just look! Every store has them piled up in mountainous heaps. They say that after nightfall jinns come and buy up everything. ‘My abba says that at midnight there is a jinn at every stall. He has all that remains weighed and pays in real rupees, just the sort of rupees we have,’ says Mohsin.

Hamid is not convinced. ‘Where would the jinns come by rupees?’

‘Jinns are never short of money,’ replies Mohsin. ‘They can get into any treasury they want. Mister, don’t you know, no iron bars can stop them? They have all the diamonds and rubies they want. If they are pleased with someone they will give him baskets full of diamonds. They are here one moment and five minutes later they can be in Calcutta.’

Hamid asks again, ‘Are these jinns very big?’ ‘Each one is as big as the sky,’ asserts Mohsin. ‘He has his feet on the ground, his head touches the sky. But if he so wanted, he could get into a tiny brass pot.’

‘How do people make jinns happy?’ asks Hamid. ‘If anyone taught me the secret, I would make at least one jinn happy with me.’

‘I do not know,’ replies Mohsin, ‘but the chaudhry sahib has a lot of jinns under his control. If anything is stolen, he can trace it and even tell you the name of the thief. Jinns tell him everything that is going on in the world.’

Hamid understands how Chaudhry sahib has come by his wealth and why people hold him in so much respect.

It begins to get crowded. Parties heading for the Idgah are coming into town from different sides—each one dressed better than the other. Some in tongas and ekkas; some in motor cars. All wearing perfume; all bursting with excitement.

The small party of village rustics is not bothered about the poor show they make. They are a calm, contented lot.

For village children everything in the town is strange. Whatever catches their eye, they stand and gape at it with wonder. Cars hoot frantically to get them out of the way, but they couldn’t care less. Hamid is nearly run over by a car.

At long last the Idgah comes in view. Above it are massive tamarind trees casting their shade on the cemented floor on which carpets have been spread. And there are row upon row of worshippers as far as the eye can see, spilling well beyond the mosque courtyard. Newcomers line themselves behind the others. Here neither wealth nor status matters because in the eyes of Islam all men are equal. Our villagers wash their hands and feet and make their own line behind the others. What a beautiful, heart-moving sight it is! What perfect coordination of movements! A hundred thousand heads bow together in prayer! And then all together they stand erect; bow down and sit on their knees! Many times they repeat these movements— exactly as if a hundred thousand electric bulbs were switched on and off at the same time again and again. What a wonderful spectacle it is!

The prayer is over. Men embrace each other. They descend on the sweet and toy vendors’ stores like an army moving to an assault. In this matter the grown-up rustic is no less eager than the boys. Look, here is a swing! Pay a paisa and enjoy riding up to the heavens and then plummeting down to the earth. And here is the roundabout strung with wooden elephants, horses and camels! Pay one paisa and have twenty-five rounds of fun. Mahmood and Mohsin and Noorey and other boys mount the horses and camels.

Hamid watches them from a distance. All he has are three paise. He couldn’t afford to part with a third of his treasure for a few miserable rounds.

They’ve finished with the roundabouts; now it is time for the toys. There is a row of stalls on one side with all kinds of toys: soldiers and milkmaids, kings and ministers, water-carriers and washerwomen and holy men. Splendid display! How lifelike! All they need are tongues to speak. Mahmood buys a policeman in khaki with a red turban on his head and a gun on his shoulder. Looks as if he is marching in a parade. Mohsin likes the water-carrier with his back bent under the weight of the water bag. He holds the handle of the bag in one hand and looks pleased with himself. Perhaps he is singing. It seems as if the water is about to pour out of the bag. Noorey has fallen for the lawyer. What an expression of learning he has on his face! A black gown over a long, white coat with a gold watch chain going into a pocket, a fat volume of some law book in his hand. He looks like he has just finished arguing a case in a court of law.

These toys cost two paise each. All Hamid has are three paise; how can he afford to buy such expensive toys? If they dropped out of his hand, they would be smashed to bits. If a drop of water fell on them, the paint would run. What would he do with toys like these? They’d be of no use to him.

Mohsin says, ‘My water-carrier will sprinkle water every day, morning and evening.’

Mahmood says, ‘My policeman will guard my house. If a thief comes near, he will shoot him with his gun.’

Noorey says, ‘My lawyer will fight my cases.’

Sammi says, ‘My washerwoman will wash my clothes every day.’

Hamid pooh-poohs their toys—they’re made of clay—one fall and they’ll break into pieces. But his eyes look at them hungrily and he wishes he could hold them in his hands for just a moment or two. His hands stretch without his wanting to stretch them. But young boys are not givers, particularly when it is something new. Poor Hamid doesn’t get to touch the toys.

After the toys it is sweets. Someone buys sesame seed candy, others gulab jamuns or halwa. They smack their lips with relish. Only Hamid is left out. The luckless boy has at least three paise; why doesn’t he also buy something to eat? He looks with hungry eyes at the others.

Mohsin says, ‘Hamid, take this sesame candy, it smells good.’

Hamid suspects it is a cruel joke; he knows Mohsin doesn’t have so big a heart. But despite knowing this Hamid goes to Mohsin. Mohsin takes a piece out of his leaf-wrap and holds it towards Hamid. Hamid stretches out his hand. Mohsin puts the candy in his own mouth. Mahmood, Noorey and Sammi clap their hands with glee and have a jolly good laugh. Hamid is crestfallen.

Mohsin says, ‘This time I will let you have it. I swear by Allah! I will give it to you. Come and take it.’

Hamid replies, ‘You keep your sweets. Don’t I have money?’

‘All you have are three paise,’ says Sammi. ‘What can you buy for three paise?’ Mahmood says, ‘Mohsin is a rascal. Hamid, you come to me and I will give you gulab jamun.’ Hamid replies, ‘What is there to rave about sweets? Books are full of bad things about eating sweets.’

‘In your heart you must be saying, “If I could get it I would eat it,”’ says Mohsin. ‘Why don’t you take the money out of your pocket?’

‘I know what this clever fellow is up to,’ says Mahmood. ‘When we’ve spent all our money, he will buy sweets and tease us.’

After the sweet vendors there are a few hardware stores and shops of real and artificial jewellery. There is nothing there to attract the boys’ attention. So they go ahead, all of them except Hamid who stops to see a pile of tongs. It occurs to him that his granny does not have a pair of tongs. Each time she bakes chapatis, the iron plate burns her hands. If he were to buy her a pair of tongs she would be very pleased. She would never burn her fingers; it would be a useful thing to have in the house. What use are toys? They are a waste of money. You can have some fun with them but only for a very short time. Then you forget all about them.

Hamid’s friends have gone ahead. They are at a stall drinking sherbet. How selfish they are! They bought so many sweets but did not give him one. And then they want him to play with them; they want him to do odd jobs for them. Now if any of them asked him to do something, he would tell them, ‘Go suck your lollipop, it will burn your mouth; it will give you a rash of pimples and boils; your tongue will always crave for sweets; you will have to steal money to buy them and get a thrashing in the bargain. It’s all written in books. Nothing will happen to my tongs. No sooner my granny sees my pair of tongs she will run up to take it from me and say, “My child has brought me a pair of tongs,” and shower me with a thousand blessings. She will show it off to the neighbour womenfolk. Soon the whole village will be saying, “Hamid has brought his granny a pair of tongs, how nice he is!” No one will bless the other boys for the toys they have got for themselves. Blessings of elders are heard in the court of Allah and are immediately acted on. Because I have no money, Mohsin and Mahmood adopt such airs towards me. I will teach them a lesson. Let them play with their toys and eat all the sweets they can. I will not play with toys. I will not stand any nonsense from anyone. And one day my father will return. And also my mother. Then I will ask these chaps, “Do you want any toys? How many?” I will give each one a basket full of toys and teach them how to treat friends. I am not the sort who buys a paisa worth of lollipops to tease others by sucking them myself. I know they will laugh and say Hamid has brought a pair of tongs. They can go to the Devil!’

Hamid asks the shopkeeper, ‘How much for this pair of tongs?’

The shopkeeper looks at him and seeing no older person with him replies, ‘It’s not for you.’

‘Is it for sale or not?’

‘Why should it not be for sale? Why else should I have bothered to bring it here?’

‘Then why don’t you tell me how much it is!’ ‘It will cost you six paise.’ Hamid’s heart sinks. ‘Let me have the correct price.’

‘All right, it will be five paise, bottom price. Take it or leave it.’

Hamid steels his heart and says, ‘Will you give it to me for three?’ And proceeds to walk away lest the shopkeeper scream at him. But the shopkeeper does not scream. On the contrary, he calls Hamid back and gives him the pair of tongs. Hamid carries it on his shoulder as if it were a gun and struts up proudly to show it to his friends. Let us hear what they have to say.

Mohsin laughs and says, ‘Are you crazy? What will you do with the tongs?’ Hamid flings the tongs on the ground and replies, ‘Try and throw your water-carrier on the ground. Every bone in his body will break.’

Mahmood says, ‘Are these tongs some kind of toy?’

‘Why not?’ retorts Hamid. ‘Place them across your shoulders and it is a gun; wield them in your hands and it is like the tongs carried by singing mendicants—they can make the same clanging as a pair of cymbals. One smack and they will reduce all your toys to dust. And much as your toys may try they could not bend a hair on the head of my tongs. My tongs are like a brave tiger.’

Sammi who had bought a small tambourine asks, ‘Will you exchange them for my tambourine? It is worth eight paise.’

Hamid pretends not to look at the tambourine. ‘My tongs, if they wanted to, could tear out the bowels of your tambourine. All it has is a leather skin and all it can say is dhub, dhub. A drop of water could silence it forever. My brave pair of tongs can weather water and storms without budging an inch.’

The pair of tongs wins everyone over to its side. But now no one has any money left and the fairground has been left far behind. It is well past 9 a.m. and the sun is getting hotter every minute. Everyone is in a hurry to get home. Even if they talked their fathers into it, they could not get the tongs. This Hamid is a bit of a rascal. He saved up his money for the tongs.

The boys divide into two factions. Mohsin, Mahmood, Sammi and Noorey on the one side, and Hamid by himself on the other. They are engaged in hot argument. Sammi has defected to the other side. But Mohsin, Mahmood and Noorey, though they are a year or two older than Hamid, are reluctant to take him on in debate. Right is on Hamid’s side. Also it’s moral force on the one side, clay on the other. Hamid has iron, now calling itself steel, unconquerable and lethal. If a tiger were to spring on them, the water-carrier would be out of his wits; Mister Constable would drop his clay gun and take to his heels; the lawyer would hide his face in his gown, lie down on the ground and wail as if his mother’s mother had died. But the tongs, the pair of tongs, Champion of India, would leap and grab the tiger by its neck and gouge out its eyes.

Mohsin puts all he has in his plea, ‘But they cannot go and fetch water, can they?’

Hamid raises the tongs and replies, ‘One angry word of command from my tongs and your water-carrier will hasten to fetch the water and sprinkle it at any doorstep he is ordered to.’

Mohsin has no answer. Mahmood comes to his rescue. ‘If we are caught, we are caught. We will have to do the rounds of the law courts in chains. Then we will be at the lawyer’s feet asking for help.’

Hamid has no answer to this powerful argument. He asks, ‘Who will come to arrest us?’

Noorey puffs out his chest and replies, ‘This policeman with the gun.’

Hamid makes a face and says with scorn, ‘This wretch come to arrest the Champion of India! Okay, let’s have it out over a bout of wrestling, Far from catching them, he will be scared to look my tongs in the face.’

Mohsin thinks of another ploy. ‘Your tongs’ face will burn in the fire every day.’ He is sure that this will leave Hamid speechless. That is not so. Pat comes Hamid with the retort, ‘Mister, it is only the brave who can jump into a fire. Your miserable lawyers, policemen, and water-carriers will run like frightened women into their homes. Only this Champion of India can perform this feat of leaping into the fire.’

Mahmood has one more try, ‘The lawyer will have chairs to sit on and tables for his things. Your tongs will only have the kitchen floor to lie on.’

Hamid cannot think of an appropriate retort so he says whatever comes into his mind, ‘The tongs won’t stay in the kitchen. When your lawyer sits on his chair my tongs will knock him down on the ground.’

It does not make sense but our three heroes are utterly squashed—almost as if a champion kite had been brought down from the heavens to the earth by a cheap, miserable paper imitation. Thus Hamid wins the field. His tongs are the Champion of India. Neither Mohsin nor Mahmood, neither Noorey nor Sammi—nor anyone else can dispute the fact.

The respect that a victor commands from the vanquished is paid to Hamid. The others have spent between twelve to sixteen paise each and bought nothing worthwhile. Hamid’s three-paise worth has carried the day. And no one can deny that toys are unreliable things: they break, while Hamid’s tongs will remain as they are for years.

The boys begin to make terms of peace. Mohsin says, ‘Give me your tongs for a while, you can have my water-carrier for the same time.’

Both Mahmood and Noorey similarly offer their toys. Hamid has no hesitation in agreeing to these terms. The tongs pass from one hand to another; and the toys are in turn handed to Hamid. How lovely they are!

Hamid tries to wipe the tears of his defeated adversaries. ‘I was simply pulling your leg, honestly I was. How can these tongs made of iron compare with your toys?’ It seems that one or the other will call Hamid’s bluff. But Mohsin’s party are not solaced. The tongs have won the day and no amount of water can wash away their stamp of authority. Mohsin says, ‘No one will bless us for these toys.’

Mahmood adds, ‘You talk of blessings! We may get a thrashing instead. My amma is bound to say, “Are these earthen toys all that you could find at the fair?”’

Hamid has to concede that no mother will be as pleased with the toys as his granny will be when she sees the tongs. All he had was three paise and he has no reason to regret the way he has spent them. And now his tongs are the Champion of India and King of Toys.

By eleven the village was again agog with excitement. All those who had gone to the fair were back at home. Mohsin’s little sister ran up, wrenched the water-carrier out of his hands and began to dance with joy. Mister Water-carrier slipped out of her hand, fell on the ground and went to paradise. The brother and sister began to fight; and both had lots to cry about. Their mother lost her temper because of the racket they were making and gave each two resounding slaps.

Noorey’s lawyer met an end befitting his grand status. A lawyer could not sit on the ground. He had to keep his dignity in mind. Two nails were driven into the wall, a plank put on them and a carpet of paper spread on the plank. The honourable counsel was seated like a king on his throne. Noorey began to wave a fan over him. He knew that in the law courts there were khus curtains and electric fans. So the least he could do was to provide a hand fan, otherwise the hot legal arguments might affect his lawyer’s brains. Noorey was waving his fan made of bamboo leaf. We do not know whether it was the breeze or the fan or something else that brought the honourable counsel down from his high pedestal to the depths of hell and reduced his gown to mingle with the dust of which it was made. There was much beating of breasts and the lawyer’s bier was dumped on a dung heap.

Mahmood’s policeman remained. He was immediately put on duty to guard the village. But this police constable was no ordinary mortal who could walk on his own two feet. He had to be provided a palanquin. This was a basket lined with tatters of discarded clothes of red colour for the policeman to recline on in comfort. Mahmood picked up the basket and started on his rounds. His two younger brothers followed him lisping, ‘Shleepers, keep awake!’ But night has to be dark; Mahmood stumbled, the basket slipped out of his hand. Mr Constable, with his gun, crashed to the ground. He was short of one leg.

Mahmood, being a bit of a doctor, knew of an ointment which could quickly re-join broken limbs. All it needed was the milk of a banyan sapling. The milk was brought and the broken leg reassembled.

But no sooner was the constable put on his feet than the leg gave way. One leg was of no use because now he could neither walk nor sit. Mahmood became a surgeon and cut the other leg to the size of the broken one so the chap could at least sit in comfort.

The constable was made into a holy man; he could sit in one place and guard the village. And sometimes he was like the image of the deity. The plume on his turban was scraped off and you could make as many changes in his appearance as you liked. And sometimes he was used for nothing better than weighing things down.

Now let’s hear what happened to our friend Hamid. As soon as she heard his voice, Granny Ameena ran out of the house, picked him up and kissed him. Suddenly she noticed the tongs in his hand. ‘Where did you find these tongs?’

‘I bought them.’

‘How much did you pay for them?’

‘Three paise.’

Granny Ameena beat her breast. ‘You are a stupid child! It is almost noon and you haven’t had anything to eat or drink. And what do you buy—tongs! Couldn’t you find anything better in the fair than this pair of iron tongs?’

Hamid replied in injured tones, ‘You burn your fingers on the iron plate. That is why I bought them.’ The old woman’s temper suddenly changed to love—not the kind of calculated love, which wastes away in spoken words. This love was mute, solid and steeped with tenderness. What a selfless child! What concern for others! What a big heart! How he must have suffered seeing other boys buying toys and gobbling sweets! How was he able to suppress his own feelings! Even at the fair he thought of his old grandmother. Granny Ameena’s heart was too full for words.

And the strangest thing happened—stranger than the part played by the tongs was the role of Hamid the child playing Hamid the old man. And old Granny Ameena became Ameena the little girl. She broke down. She spread her apron and beseeched Allah’s blessings for her grandchild. Big tears fell from her eyes. How was Hamid to understand what was going on inside her!

***

Translated from the Urdu by Khushwant Singh. Excerpted from ’99: Unforgettable Fiction, Non-fiction, Poetry & Humour’ by Khushwant Singh.

***