There is a vast cultural movement emerging from the Global South and sweeping all before it. India’s Shah Rukh Khan, after all, is the most popular actor in the world. Bollywood, Turkish soap operas called dizi, K-pop and other aspects of Eastern pop culture are international in their range and allure and the biggest challenger yet to America’s monopoly since the end of World War II.

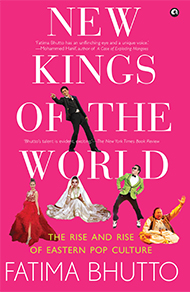

Bestselling author Fatima Bhutto’s new book is about these new kings of popular entertainment in the twenty-first century. Carefully packaging not always secular modernity with traditional values in urbanized settings, they have created a new global mass culture that can be easily consumed, especially by the many millions coming late to the modern world and still negotiating its overwhelming challenges.

The book features the author’s exclusive interview with Shah Rukh Khan. Here is the first part of the conversation.

The 1,200-square-meter Imperial suite at the Palazzo Versace seemed to conform to the unrestrained aesthetic of Arabian Gulf autocracies. All available surfaces—lamps, tables, plates—were emblazoned with Versace’s gilt Medusa heads, baroque urns and flowery motifs. It is more than just a hotel room, it has its own ecosystem. There is a grand staircase leading to the second floor, three chandeliers in the sitting room alone, a private butler on call, a long dining table set for ten, and the Indian Premier League playing on a huge flat-screen TV. I’m trying to see which team is playing* when he walks in.

“As salam alaikum,” Shah Rukh Khan greets me as he settles into a Versace chair. He’s wearing a black hoodie, camouflage trousers, and scuffed Converse sneakers. Khan radiates a sunny boyishness rather than matinee idol hunkiness. He is not as imposingly tall as Bollywood’s previous superstar, Amitabh Bachchan, and has bulked up in recent years—obliged by Bollywood’s new ideals of masculinity to take his shirt off for work, Khan now sports a tight, sinewy musculature. His impressively black hair flops, when not slicked back into his standard quiff, over his forehead, and across his dark brown eyes. He smiles often but shyly, checking first to see if you’re smiling too. If you are, the hero’s full lips widen and dimples appear in his cheeks. Tonight, he appears tired and sunburned.

We were scheduled to meet tomorrow when I will accompany Shah Rukh to a shoot for an Egyptian television show but even though he’s just stepped off a sixteen-hour flight from California, I got a call asking me to come tonight. We have some time to talk before he heads back to work at 11 p.m. when Alia Bhatt, Shah Rukh’s co-star from Dear Zindagi will arrive for a script narration.

“I’m watching all your films,” I tell him.

“I’m sorry,” he laughs, sheepishly.

“I’ve seen seven in the week before traveling.”

“Twenty hours of your life,” Khan estimates.

“One part says that I came into the film industry when India was opening up, the Indians in the diaspora—including Pakistan and Bangladesh, I mean the whole South Asia has the same status—were all proud suddenly having Indian movies to be watched and second generation and third generation people were being made to watch these by the first generation to teach them culture, to show them this is hamara land,” Khan reflects.

“Somehow, I led the movement because the kind of films I did were a mix of being cool, which I think people abroad wanted themselves to be felt like. So I was cool enough and we were traditional enough.” Others felt that it was because he stood for the youth in India, or because he stands for self-made success, having entered the business with no backing. “Why I’m saying all this is because I think none of it is true.” There’s something more to it, Khan says of his superstar status, and something less.

He speaks animatedly, no matter the time and no matter how tired—or in fact, how long he has been speaking—with bouncing emphases and stresses, flip-flopping between Hindi/ Urdu and his British-inflected, subcontinental English. “Is that how you pronounce it?” he often asks—checking or warning that he might mutilate “Cannes” or “asphalt” or “Y Tu Mamá También.”

Abhinav, a white-gloved Indian butler, brings a small espresso cup and places it down on the side table next to Khan. He rips open a sachet of sugar and pours it into the coffee, stirring it gently, before crumpling the sachet into the ashtray, which he discreetly replaces with a fresh one. The whole while, neither looking exactly at Khan nor very far away from him, the gloved butler wears a mask of serene adoration.

“I’ve never been a straitjacketed proper hero in my films.” Khan continues. In Baazigar, “I take a girl up a terrace and throw her off and you’re okay with that. I don’t know why. I don’t watch my films but I remember when that film released most of the kids were loving it. And it’s so gruesome!

“There’s a certain sense of goodness I bring to badness. People trust me with badness. You know, normally people trust you if you’re good. I think there’s an inherent quality that you trust me with the badness. You say, it’s okay if he’s going to be bad, he’s not going to be really bad.” Even though he’s dressed like Justin Bieber, there is something avuncular about Khan.

“Why can’t the Bollywood hero win?” I ask. “Why can’t he ever catch a break?” There’s no defying family, no getting the girl he loves, nothing—whereas in Hollywood if the hero’s aims are noble, he can defeat any obstacle.

“Sacrifice is a big part of our culture,” Khan replies. “We’re taught to sacrifice from childhood, in our religion—in all the religions of South Asia—you’ll only be told stories as you grow up of how heroes gave up things to achieve things for themselves but mostly for others.”

In Hollywood, obstacles can be personal and therefore overcome, Khan continues, but in India, your sacrifices are for others. “So if I did not marry in a film…the girl I love, it would be because I want her to marry the elder brother in the family because he’s the one who’s of the right age. Now if you were to see this in the context of the West, there’s nothing like age, stage or even brotherhood of that level.”

Abhinav appears like a shadow and sweeps away another coffee cup.

“The most successful directors in the country right now, they only look for roles where I’m going to rise above human nature,” Khan shakes his head. “They always make me do roles like that, even if I’m just a dance trainer.”

Presumably, that’s why Khan never swears in his films. Tomorrow, during shooting, I will hear some classic swearing—but for now, at least until I ask the question, there hasn’t even been a single dip in the language.

Khan offers me green tea which seems more appealing than coffee two hours from midnight. I ask if he’d ever do a Hollywood film and he claims he’s never been offered one. “And I have a secret dream which is not a secret: I want to make that Indian film—participate in that Indian film—which is watched by the world.” He’s considered stories from the Hindu religious texts, the Mahabharata or the Ramayana, but feels that for such a film to go global it would have to have cutting edge FX, fewer songs, no interval and be standard movie length, only an hour and a half long.

“Good luck getting the Mahabharata into an hour and a half,” I say. Like a savvy producer, SRK waves his hand in the air.

“There’ll be sequels and prequels.”

“A movie seen by everyone on earth doesn’t seem that far off?” I suppose out loud.

“Inshallah,” Khan replies solemnly, sipping his coffee.

Khan has fans all over the world, including a coterie of eight to ten elderly German ladies who have followed him everywhere he goes for the last twenty years, watching him lovingly from the sidelines. It’s fulfilling for me, he insists, interacting with these fans. “A lot of it has become about selfies now but I can feel there’s a little more to them. I fulfill some incompleteness about their lives which I don’t know about. It could be a young girl who dreamed of marrying a guy like Raj* and she did not and now she’s settled, she’s got two kids, but the dream still lives on so when you meet her it’s like ‘I met my Raj!’ and I don’t have the heart to tell them I’m not Raj. I don’t know, maybe your husband is a billion times better than that life you would have had with Raj…yeah, it’s a very strange kind of…when you go for a live show people are screaming and shouting and all that happens but in quieter places, people will just come and say, ‘Can we touch you?’”

He whispers the last line.

It’s nearly 11 p.m. and time for his narration. We leave for shooting tomorrow at noon sharp, Pooja, Khan’s PA, a small, stout woman in her early thirties says, it’s a tight schedule. I promise to be on time.

“Khuda hafiz,” Khan says in Urdu as I’m leaving the Imperial suite.

“Khuda hafiz,” I reply. May God protect you.

Mithun—“not Chakraborty”—the twenty-nine-year-old chauffeur from Kerala who will be on duty during Shah Rukh’s time in Dubai, wants to know everything as soon as I get into the car, which Khan insists will drop me back to my hotel given the late hour: What was Khan like? What did he say? What am I writing? Do I always write about Khan? Did I know him from before? Have I seen his movies? Mithun told me that he had driven everyone—including Kim Qadir-shee-an, a model who was being filmed the entire time she was in his car, in fact, he never saw her face, and they were followed by police escort “all for this one girl”—but no one was as truly wonderful as Khan. “He started from jero. He had nothing. When I am born, that time also he was an actor. He looks the same,” Mithun rhapsodized, “No changing, no different…”

“All love stories and we like his body language too,” Mithun sighs as the lights of Dubai’s skyscrapers and construction cranes glitter in the dark. “He’s a genius, eh?”

******

You can read the second part of the interview in New Kings Of The World. Get the book here: https://amzn.to/2m5XmO3